Winter Skin Problems in Horses

There are a number of skin problems and infections that affect horses, some of which are more frequently seen in winter and wet conditions. Dr. Greg Evans, co-owner of Moore Equine, near Calgary, Alberta, says that in his practice the following are several common skin problems he deals with.

Scratches

“I think inconsistency in weather and a constantly changing environment can be harder on the skin than a more consistent climate. If your winter is wet and muddy or alternately dry and wet, this is tough on skin. If horses are standing in mud or have to walk through muddy areas in their pen or pasture, scratches is the number one skin condition we deal with. There are several names for this, including greasy heel and mud fever. The medical term is pastern dermatitis,” says Evans.

“The cause is not always known, but it occurs most frequently in wet conditions. We think there is likely some micro-trauma to the skin of the pastern—maybe a nick or abrasion. In winter, the skin might be broken by ice or crusted snow. If moisture is held against the damaged skin by hair, especially in horses that have a lot of hair on the lower legs, this seems to make them more susceptible,” he explains.

The precise causative organism has never been definitively cultured. “It’s usually a mixed bag of bacteria and fungi that are present in the mud and fecal material the horses are standing in. It starts as a wet rash on the leg/pastern/heel area and then becomes a crusted scab. The lesion can spread aggressively. In our practice, scratches tends to most commonly affect horses with white legs.” Pigmented skin seems to be a little tougher and less readily nicked and scraped. Horses with white “socks” usually develop lesions only on the white legs.

“There are differences of opinion regarding treatment,” says Evans. “In my practice, I like to sedate the horse and clip the legs to get all the debris and crusted hair removed. Sometimes I can do this with just a salve containing moisturizers, antibiotic and a little bit of steroid, to soothe the sore pasterns and soften the scabs so we can lift them off. Then we can clip around the area.

“I clean the affected area with chlorhexadine soap and thoroughly dry the legs. I tell clients that it is very important to dry the area very well with a towel or hair drier. One of the problems with scratches and why it lingers for weeks is that clients are continually washing the lesions and leaving the legs wet. Because the microbes that cause scratches have an affinity for wet conditions, this delays healing.”

This is also good reason to not bandage the area. “Some people like to bandage the leg after cleaning it and applying medication, but I personally prefer to leave it open,” he says. “A bandage holds moisture and exudates against the skin. I prefer it to be dry. If the environment/management is such that the feet cannot be kept dry because the horse lives outside in the rain and mud, it becomes a real problem.

“If there’s opportunity to keep the legs dry, I like to meticulously dry the lesions and keep the horse indoors in a dry stall, with good hygiene so there’s not much urine and ammonia in the bedding. If possible, we let the horse out on a nice paddock where the sun can get to the lesions and where the feet are not buried in mud.”

Scratches can be frustratingly slow to heal and may come back again. “Typically I don’t use antibiotics unless the horse is exhibiting other signs of subcutaneous infection like significant limb swelling or lameness associated with the scratches,” he says. “In early stages, I just use local treatment with topical ointments. But keeping it clean and dry is most important.

“The other group of horses in which I see a lot of scratches is show horses or any horses that are bathed a lot. They aren’t standing around in muddy paddocks, but frequent excessive bathing leaves the legs wet and this is hard on their skin.” It’s just like human hands being continually wet and dry, wet and dry. The skin tends to chap.

“Even though the owners want their horses clean and shiny, this is not the best for the skin,” he says. “We create a situation where we set the horse up for inability to adapt; the skin never knows whether it will be wet or dry.

“A complicating factor in scratches, because there’s very little agreement on the cause, is that people tend to use a variety of pharmaceutical and chemical treatments. Since this is a frustrating disease and doesn’t go away quickly, horse owners may get overzealous with the number of treatments they apply—using various soaps, salves, and sometimes caustic medications. These may deter healing by creating chemical damage to the surrounding skin, in addition to the initial lesions. I’ve seen cases where a relatively minor infection got out of hand, and I suspect it had something to do with an overzealous owner using multiple chemical treatments simultaneously. The horse owners or trainers are trying to do what they can and may get carried away because there are many people giving different advice and opinions on treatments.

“Here at our clinic we have a pharmacy technician who does a lot of our compounding,” says Evans. “Our scratches ointment is a mixture of zinc ointment, a little furacin, penicillin, and a little bit of corticosteroid to help decrease the swelling and reactivity of the skin. We use this cream fairly liberally at first, to soften the crusts so we can take them off and get them out of the way. Once we get the wound cleaned up so there are no crusts or debris, we use it more sparingly to allow dry air and sunlight to get to the area. I think sunlight and fresh air can help it heal. This not only helps scratches, but also some of the other skin lesions like ringworm.

“Many skin problems will readily heal—and we call those self-limiting—if the horse is out in the sunlight, whereas if the horse is blanketed all the time and kept in a barn where it’s damp and there’s ammonia in the air, this makes things worse.”

Sometimes other infections, like bacterial folliculitis, can look similar to scratches but is not as common. “It is similar to what is seen in dogs and humans, with bacterial infections of the hair follicles and secretory glands of the skin,” he says. “There are some types of bacteria that are normally found on the horse’s skin, such as various staphylococcus and streptococcus species. If there is trauma to the skin, or if the horse has a lot of fly bites, the bacteria have access and can invade the follicles. It’s like acne in that it can appear almost anywhere on the horse. It tends to look a little like scratches at first, but has a greater distribution. Scratches (pastern dermatitis) is almost always limited to the back of the pastern initially, whereas these other infections may start anywhere on the body or face.

“There are usually multiple firm nodules. Sometimes there is crusting. There may or may not be any hair loss. The lesions usually are not itchy, but the client is generally worried about the spreading nodules. For diagnosis, we take a skin scraping or skin biopsy to view under a microscope. We usually identify a lot of white blood cells and sometimes we can see active bacteria.

“Most of the time when I arrive at this diagnosis, the client has been treating it as scratches (and maybe didn’t involve the veterinarian) and has become frustrated. When I look at it, I can see that it’s not typical scratches and do a biopsy. Then the pathologist finds a staph infection. Those require a different course of treatment,” Evans explains.

Rain Rot (Rain Scald)

“We don’t commonly see this in a dry climate, but rain scald is probably the second most common wet-weather skin problem in horses,” says Evans. “In my practice, we see it mainly in winter when horses have snow on their backs and it melts and runs down their back, similar to a horse that’s standing out in the rain a lot.

“The causative organism is Dermatophilus congolensis, which is a flagellated anaerobic bacterium. It’s probably a prehistoric bacterium, compared with some of the others such as staph and strep. The pathogen that causes rain scald has more ancient DNA.

“There are probably carrier horses, and if conditions are right they can spread it to other horses through direct contact. Rain or wet conditions may trigger active infections if there’s a break in the skin. Horses with rain scald have a typical crusting hair loss, generally on the topline and down the buttocks and neck—but predominantly over the back, shoulders and rump. Rain scald tends to have a recognizable clinical appearance; the lesions almost look like water beading off the horse, like a drip pattern. The crusts generally correspond with that pattern.

“We can examine samples of the crusts under a microscope and see the flagellated bacteria. They have what’s called a railroad track pattern. These skin scrapings are diagnostic and we don’t have to send them to a pathology lab; we can usually recognize them ourselves,” Evans says.

Treatment is topical. “We like to keep these horses dry,” he explains. “We first wash them really well with chlorhexadine soap to remove the crusts and then apply a chlorhexadine ointment to the affected areas. Generally, the lesions respond favorably if we can then keep the horse dry. If the horse lives outside and we’re having constant rain, I encourage the client to keep that horse inside. If we’ve just come through a rainy period and the client recognizes that the horse has rain scald and we’ve treated it, and we now have nice weather, I like to see those horses out in the sun, in dry conditions.”

Rain scald can be a cosmetic issue because a large area of the horse may be affected, with hair loss. “Clients wonder if the horse is contagious, but if you are actively treating the horse and keeping it dry, this condition is not any more contagious than the horse was prior to getting it,” he says. “We don’t know which horses are carriers; we generally just treat the affected individuals.

“Rain scald is generally not as frustrating as scratches, because scratches tends to recur over and over again, if conditions are right. Rain scald seems to be more of an intermittent problem, depending on the weather.”

Rain scald lesions can be painful, and the horse may not be able to wear a saddle until these areas heal. “In some cases we have to use anti-inflammatory drugs, such as non-steroidal drugs like phenylbutazone to manage acute pain. On occasion, in horses that seem to have an auto-immune component, I use low dose steroids for 7 to 10 days to get the pain and swelling under control. Most of the cases I see, however, are not very painful—particularly if we get the crusts off. The chlorhexadine cream acts as a soothing salve,” Evans says.

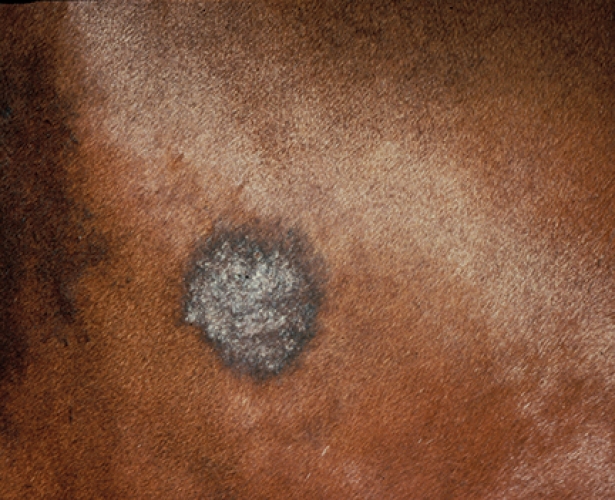

Ringworm

“This is another common infectious condition,” says Evans. “The medical term is dermatophytosis; the fungal organism is a dermatophyte that lives on skin. There are a number of fungal organisms that can cause ringworm. Most of them can affect all species and not just horses. When a horse has ringworm, it could be spread to humans and other animals. I encourage horse owners to be careful and use gloves when handling or treating the horse. If their immune system is suppressed for any reason (stress, chemotherapy, etc.), they would be more likely to get it themselves.

“We typically see ringworm in a random distribution. It is not as dependent on weather or management. The horse may have a suppressed immune system for some reason and this allows the fungal organism to become established. Signs are patchy hair loss—anywhere on the body, but typically on the trunk, head and neck. We don’t see lesions as often on the limbs.

“One of the characteristic signs, if you examine around the margins of where the hair is lost, is that you can easily pluck the hair. It readily comes out in tufts around the edges of the hairless area. This is different from a typical rub mark that some people might think is ringworm. If I tug on the hair around the margins, and it comes out in tufts, I am suspicious of

fungal infection.

“Diagnosis can be made with a skin scraping, or even a plucking of the free hair. It is easy to see fungal elements on a microscope slide. Sometimes I biopsy a lesion, depending on how aggressive it is. Some horses are itchy with ringworm and some are not,” Evans says.

Humans may play a role in transmission by using the same tack and grooming tools on different horses, or by not being careful about bio-security issues. “It can spread rapidly amongst a group of horses if people aren’t careful when handling an infected horse,” he explains.

Ringworm can heal spontaneously in one to six months, especially if the horse is outdoors in the sunlight—which is one reason it’s not as common in summer as in winter, but some horse owners choose to treat it. “If it occurs in a group of weanlings out in a pasture, you might just let it run its course,” he says.

To treat ringworm, he recommends bathing the horse using a horse shampoo. “Rinse the horse well, and while he is still wet, apply a lime-sulfur mixture. There are also commercial products available. Most of them are made for small animals, but the two key ingredients (lime and sulfur) also work for ringworm on horses,” says Evans.

“I have the client sponge the mixture onto the affected areas, let it sit for half an hour, and then rinse the horse off really well. If the condition does not resolve within a week, I have them repeat the treatment. Only rarely do I need to examine a horse again after two treatments.”

Some people use diluted bleach to treat ringworm. “I haven’t used it myself because I’ve had good luck with the lime-sulfur, and bleach seems like it would be a bit caustic,” he says. “If you don’t get the dilution correct, you might end up burning the horse’s skin or yours, or stain your clothes. Sulfur smells bad but it’s not as harsh as bleach.”

Urticaria (Hives)

Hypersensitivity reactions may produce hives or welts in the skin. This may happen at any time of year, depending on what the horse is exposed to. “The horse may break out in hives for unknown reasons. The client is often concerned about allergies, but often it’s more of a hypersensitivity to something the horse has come into contact with. As an example, a harsh detergent used on the horse’s blanket, or new hay, or new load of shavings that’s come into the barn (for bedding) that has a different chemical treatment,” says Evans.

Occasionally, a certain horse is reacting to the adjuvant in a particular vaccine or has a drug sensitivity. “The owner may have tried a new joint supplement and the horse reacts,” says Evans. “The history is very important in these situations, to see what the horse has been exposed to. Have there been feed changes, new bedding material, medications given, topical sprays or any other things that might explain why this horse may have suddenly become sensitive?

“I encourage clients to make incremental changes in the horse’s management to see if the horse improves. Commonly the problem is due to contact with something, or an environmental allergen. Food allergies are rare in horses, but do exist.

“The hives may be patchy over the neck and shoulders, or over the whole body. In an acute case, we give the horse a little bit of antihistamine and steroids to try and decrease the reaction. Once we have it under control, we wean the horse off the steroids and ask the client to make small changes to the management of that horse to see if they can identify the cause of the problem—if we haven’t been able to figure it out from the history. We ask the client to remove one variable at a time and note when the problem goes away, doing a process of elimination, if possible. Then if we can identify what the causative situation is, we remove that from the horse’s environment or management.”

There are some reactions, however, that may occur only once in a certain season and you are guessing at the diagnosis, thinking it may have been some sort of insect attack or a spider bite that caused a rapid and acute response. “Unless the same insect bites the horse again, it may never happen again.”