Mucous Membranes

by Nancy S. Loving, DVM

It seems fitting to walk you through some basic evaluations you can do on your horse when you think he may be out of sorts. This provides you and your veterinarian with specific information that may need to be acted on immediately. In this first installment, let’s focus on mucous membranes.

When evaluating the overall health of a horse, it is common to focus on the obvious – the bloom of the hair coat, the horse’s attitude, his posture and stance. Yes, there is another useful clue about the health of the internal workings of a horse: the mucous membranes, which line body cavities, and are visible wherever skin interfaces with a body opening, such as the gums, the vulva, the prepuce and penis, inside the nostrils and the conjunctival sac of the eye. These membranes secrete viscous mucus that keeps them moist and protected, and they are also well supplied with blood to provide useful information about the circulatory status of the horse.

Mucous Membrane Color

Mucous membranes are a reflector of internal health as they reveal the efficiency of the heart as a pump and the capacity of vessels to carry the blood circulation to the periphery. When an adequate supply of oxygenated blood is carried to all areas of the body, the color of the gums is similar to the pink hue beneath your fingernails. Any departure from this pink may mirror an internal change.

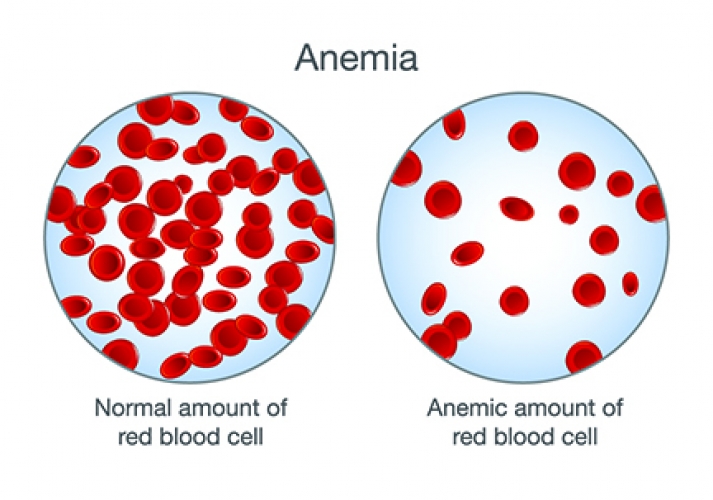

Paleness indicates a reduction of red blood cells and/or oxygen in the peripheral circulation. This may result from blood loss or dehydration. Anemia is a deficiency of red blood cells or hemoglobin related to blood loss (acute or persistent) or chronic bacterial or parasitic infection. Chronic blood loss occurs with leakage from the gastrointestinal tract, such as with bleeding gastric ulcers or with excretion through an inflamed urinary tract. Tissue necrosis related to cancer of internal organs also consumes red blood cells.

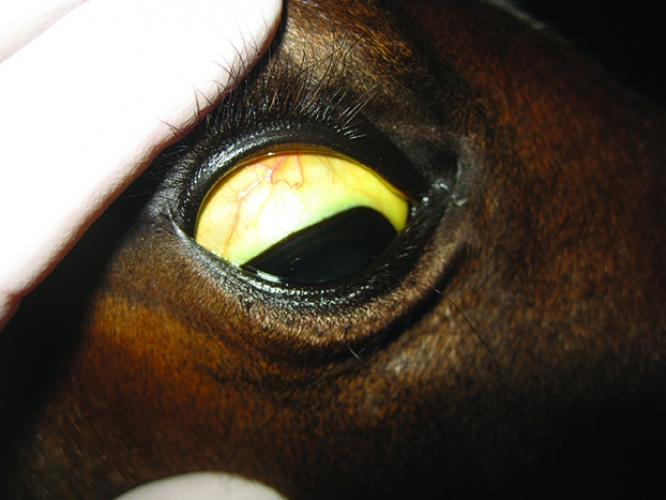

A yellow tinge to the mucous membranes reflects jaundice, which may be transient due to diminished appetite and food intake or to a diet rich in alfalfa but could be more lasting and serious as a result of liver disease.

Various lighting conditions may lead to inaccurate interpretation when assessing mucous membrane color, particularly in the presence of fluorescent lights, a flashlight, or in dim or dusk ambient light conditions. Regardless of activity, whether a horse is resident on the farm, used in casual recreation, or participates in extreme exercise stress, pre-existing conditions may confound mucous membrane evaluations. Evaluation can also be difficult in horses that object to anyone looking in their mouths and poking around on their gums.

Capillary Refill Time

Finger pressure on a horse’s gums blanches away the color as blood is pushed aside in that location. The membranes should pink up again as blood refills within 1 - 2 seconds, referred to as capillary refill time (CRT). This measures the amount of circulating blood volume and blood pressure. Refill time varies slightly, dependent on the amount of pressure exerted by a pressed fingertip. Mucous membrane color evaluated with the CRT is a fundamental hydration factor evaluation that directly correlates to perfusion of other body tissues, especially the bowel. This has significant consequences to an exercising horse or to any horse suffering from gastrointestinal disease or colic.

When assessing mucous membranes, the amount of saliva present on the gums is telling of the degree of hydration in the whole body; a dry, tacky mouth often indicates dehydration.

Reflection of Systemic Health

Whether a horse experiences dehydration as he is participating in an athletic event or transport, or is suffering from gastrointestinal disease or any illness, mucous membranes serve as a monitor of the cardiovascular status of the horse. Performance horses not only contend with fluid shifts to demand tissues such as heart and muscle for locomotion and brain and kidney for normal homeostasis, but they also must contend with fluid loss as sweat to maintain thermoregulation.

The first aberration of the color of the mucous membranes as a horse dehydrates and/or responds to fluid shifts is a reddening of the mucous membranes above the tooth root with a corresponding paleness to the rest of the tissue. This is first appreciated as a disparate color along the membranes, referred to as margination, which casts a purplish or bluish tinge along the line of the teeth while above the gumline appears pale or even normal pink in color.

Circulatory compromise may progress, and if there is limited compensatory adjustment, the mucous membranes will continue to pale, taking on a bluish tinge, and finally turn a purple, muddy color. Commonly, changes in mucous membrane color (paling) are accompanied by a delay in the CRT of greater than 1 - 2 seconds. If dehydration and fluid shifts sufficiently compromise perfusion of the cecum and/or large bowel, endotoxemia may affect the capillary beds and result in a “brick red” color to the mucous membranes. Septic or endotoxic shock causes peripheral vascular beds to open, with increased filling of blood in the capillaries and small vessels. As circulatory shock progresses, less oxygen is sent to the tissues, so this congested blood stagnates, loses its oxygen, and the membranes turn purplish or blue-tinged, then eventually turn to a deathly, muddy-gray.

The Colicky Horse

A horse suffering from systemic illness, such as gastrointestinal disease or colic, is at risk of deterioration of the circulatory system – this is often revealed by the character of the mucous membranes. Mucous membrane color has some predictive value for survival but is not a completely reliable parameter. If a colicky horse has pink mucous membranes, studies indicate that there is a greater likelihood of survival (55%), whereas a horse with toxic, cyanotic, or injected mucous membrane color has a less likely chance of survival (44%). This is not much of a statistical difference, but is more useful following surgery, when membrane color is better correlated with survival probability: If the color is pink after surgery, that horse will likely live.

Determination of survival prognosis in colic cases is better correlated with the CRT. Rough estimates of survival suggest that with CRT less than 2 seconds, there is 90% survival, a survival rate of 53% if CRT ranges between 2.5 - 4 seconds, while only 12% survive if CRT is greater than 4 seconds.

Corroboration with the Entire Clinical Picture

Although mucous membranes are telling of the ability of the heart to pump blood and the dispersal of oxygenated blood to the periphery, it is not the only physical parameter used to evaluate the health of a horse. No one parameter should be used to evaluate the metabolic status of a horse whether it be the fitness of the horse to accommodate the stress under which it performs or its status during a crisis of illness. For an exercising horse, if only one parameter could be evaluated, it would be the heart rate. Evaluation of the heart rate and its recovery following exercise encompasses more physiological parameters that any other single measurement.

Heart rate is also a prognostic parameter useful to assess a horse with colic. Elevations in heart rate occur because of pain, dehydration, endotoxemia, and shock. The higher the heart rate, the worse the prognosis. A colicky horse has a 90% survival rate if the heart rate remains below 60 beats per minute (bpm). At heart rates between 60-80 bpm, a horse has 50% likelihood of survival, and at 80–100 bpm, only a 25% survival rate. Heart rate exceeding 100 bpm correlates poorly with survival – only 10%. The temperature of a horse’s limbs, ears, and muzzle also reflect peripheral blood perfusion; cold extremities and ears and cold, clammy skin are signs that corroborate cardiovascular shock and poor survivability.

With regards to an exercising horse, it is appropriate to gather a full clinical “picture” of a horse’s physical status to use in conjunction with evaluation of the mucous membranes. Other important evaluations of an exercising horse include auscultation (with a stethoscope) of the abdomen in all quadrants to appreciate quality and frequency of gut sounds, palpation of muscle tone in the croup and hamstrings, and assessment of anal tone reflex. Jugular filling gives a relative impression of blood pressure, as does the quality of the peripheral pulses of other large blood vessels such as those monitored on the face or along the lower limbs. A more subjective, but equally important, factor is the horse’s demeanor. Does the horse appear engaged in its surroundings, or does he seem “checked out?” Does the horse want to eat and drink? Does the horse wag its head side to side when asked to trot? Does the horse ‘snirl’ its nostrils and/or have a dull, glazed expression?

Other Disease Reflections

Because mucous membranes are sensitive and informational, they are an alert for other disease syndromes that are apparent with visual inspection. Blisters, vesicles, or ulcers may form subsequent to inflammation or due to a systemic disease process. Examples of pathologic conditions that cause blistering of the mucous membranes of the mouth, in particular, include vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) or blister beetle toxicity. While VSV is accompanied by blisters or ulcers within the tissues of the mouth, nose, and bordering skin, ingestion of even a portion of a blister beetle hidden in alfalfa hay creates inflammation and necrosis along the entire internal mucosal lining into the bowel and is not isolated only to the oral or external tissues. VSV also can elicit vesicles on the mammary gland or prepuce or penis, while crusty vesicles develop due to some infections with equine rhinopneumonitis virus.

Mucous membranes possess some absorptive capacity that may be useful in administering medications, yet this characteristic may be harmful if membranes come in contact with toxic substances. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug toxicosis (as for example with phenylbutazone or flunixin meglumine or ketoprofen) may create oral ulcers concurrent with the development of gastric ulcers. Caution should be taken when applying caustic or irritant substances like leg paints and blisters or when painting a fence with chew-stop products; a horse might lick or touch any of these with his mouth, setting up an adverse reaction that may be difficult to interpret without diligent sleuthing to discover the source of the problem. Ingestion of certain toxic alkaloid-containing plants also can elicit mouth blisters.

Vasculitis describes an illness associated with leakage of blood vessels. Collection of red blood cells in the surrounding tissues is often visible as tiny red spots on the mucous membranes. Such blood spots (petechiation) develop from a vasculitis event such as occurs with equine viral arteritis (EVA), equine rhinopneumonitis virus, or due to purpura hemorrhagica, which is an allergic response subsequent to previous infection with Streptococcus equi bacteria.

Typically, a systemically sick horse demonstrates other abnormal physical signs associated with many of these illnesses, such as an elevated fever and poor appetite related to pain with eating. Slobbering and excess salivation often accompany mouth pain or irritation. There may be localized swelling or edema, or hives related to some systemic illness. Mechanical problems, such as foxtails and weed seeds that embed in the gum margins cause an abnormal appearance to the mucous membranes, sometimes accompanied by an unwillingness to eat. When inflammatory conditions involve the mucous membranes of the eye, the horse will be troubled by associated swelling, engorgement of blood vessels, and other signs of ocular inflammation, such as tearing and pain.

Cancer, most commonly squamous cell carcinoma, is a disease process that often develops directly in mucous membranes. The most likely locations for this cancer are the ocular membranes such as the sclera or the third eyelid, the penis or prepuce of a male horse, on the vulva of a mare, or around a non-pigmented anus. Squamous cell carcinoma can be invasive over time, but external cancer lesions are managed well with cryosurgery to freeze affected cancerous tissue. Mucous membranes lining the stomach and other internal organs are also prone to squamous cell carcinoma. Because this internal form of cancer is more insidious and lurking, it is not readily identified until a horse shows clinical signs of major systemic effects, often beyond the scope of treatment options.

Next Time

In the next installment, we will look at the Significance of Gut Sounds. Stay tuned!